If you are just starting to engagement ring shop or just collecting inspiration for your Pinterest boards, you may have encountered some new lingo or terminology about engagement rings. While an engagement ring might seem simple, there are several design features that go into each setting. Knowing how to differentiate these parts can help you to fully explore your options during the buying process and communicate those preferences to a jewelry specialist or your partner. Read on to learn more about the anatomy of an engagement ring with our guide!

What are the different parts of a ring called?

Center Stone

The center stone is the largest diamond or gemstone that sits directly in the center of the setting. It is the star of the show and one of the most highly considered parts of the engagement ring. While the most popular shape for a center stone is round, fancy diamond shapes including oval, pear, emerald, cushion, marquise, and radiant cut diamonds are becoming an increasingly popular choice.

Side and Accent Stones

Side or accent stones are the stones that flank the sides of the center gem and are attached to the shoulders or the shank of the setting. Side stones can either be made up of diamonds or gemstones and can come in any range of fancy shapes for a truly unique look. Accent stones can either span just a portion of the ring or fully encircle the entire band in an “eternity” style.

Setting

Engagement ring settings include every part of the engagement ring but the center stone and refer to how stones are set or mounted on to the band. The setting’s purpose is to support and highlight the beauty of the main center stone. The style of your setting can dramatically affect the overall final look, performance, and maintenance of your engagement ring. Settings are often broken down into distinctive style categories. Below are six of the most common:

- Solitaire: Solitaire engagement ring settings are classic and eternally popular. They feature an all-metal band and a singular center stone, placing all the focus on the center gem. Solitaire settings can easily be made more stylized by pairing them with a diamond-accented wedding band.

- Halo: Halo engagement ring settings feature a singular enter stone that is completely encircled by smaller gemstones for a dazzling look. Halo engagement ring settings often make the center diamond appear larger in size and are ideal for someone who is looking for showstopping sparkle.

- Three Stone: Three stone engagement ring settings are highly sought after for their added sparkle and symbolic meaning. This setting features a main center gem with two smaller accent diamonds on each side. The three stones represent the journey a couple takes together – past, present, and future.

- Hidden Accent: Engagement ring settings featuring hidden diamond accents are becoming an increasingly popular choice. The accents can be found hidden in a halo under the center stone, diamond accented bridge, or a diamond adorned gallery. Hidden accent engagement ring settings sparkle from every angle for a truly dazzling effect.

- Bezel: Bezel engagement ring settings are the most secure as the outer edge of the center stone is completely enclosed with a layer of precious metal. This securely holds the center stone in place and creates a contemporary look.

- Pavé: Pavé engagement ring settings feature a band that is mounted with tons of tiny diamonds that are set close together for a diamond encrusted look. This setting is perfect for the bride looking for an extra pop of subtle sparkle.

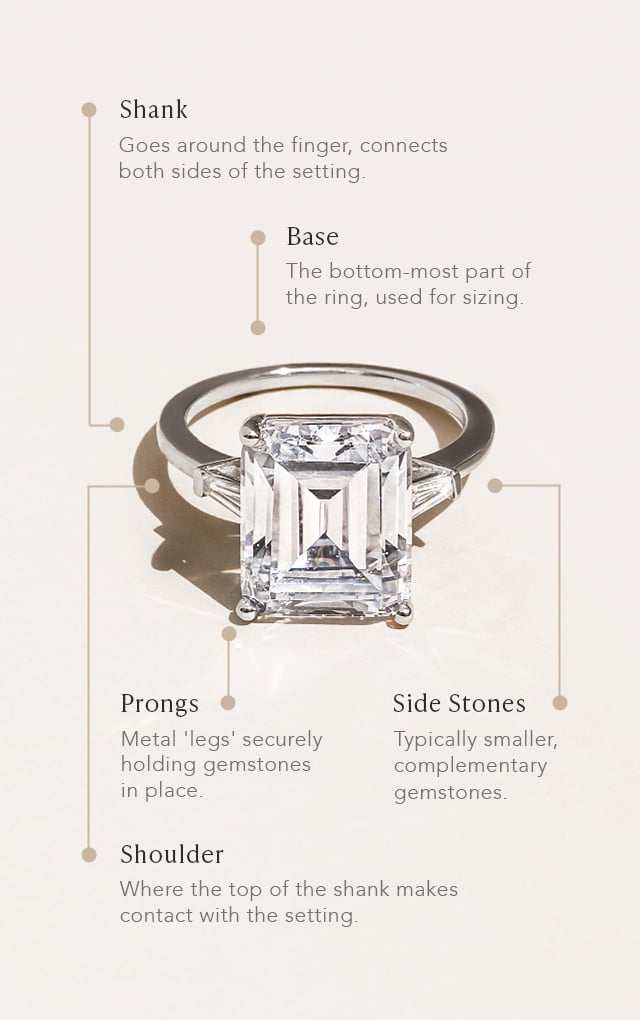

Head

The head is located at the top of the engagement ring and refers to the part of the engagement ring that holds up the center stone. The head includes the prongs and gallery.

Prongs

Prongs are the small metal tips that hold the center stone in place. They are either claw prongs which have pointed ends, bead prongs which are rounded, or sometimes V-shaped depending on your setting and center stone shape. Engagement ring settings most often feature four or six prongs, although some fancy diamond shapes such as a pear may require an odd number.

Gallery

The gallery is part of the head and refers to the detail on the underside of the ring center stone that you can see from the side profile. The engagement ring gallery is a place to feature intricate design details such as hidden diamond accents that add to the unique beauty of the ring.

Bridge

The engagement ring bridge is the part that rests on top of the finger and can be found under the head. The bridge increases support for the head and is often a place that includes added design details such as diamond accents or a milgrain pattern.

Shoulder

The engagement ring shoulder refers to the top sides of the engagement ring that form the beginning of the shank. The shank can be twisted, flat, curved, or included other unique design details.

Shank

The engagement ring shank, commonly referred to as the band, is the metal part of the engagement ring that encircles your finger. The shank starts at the end of the shoulders and is typically all-metal, but can feature diamond accents that extend around the entirety of the shank – which is called an eternity band. The shank is an important design element affecting both the appearance of the ring and how it feels to the wearer.

Sizing Area

The sizing area is the bottom portion of the shank where the ring can be cut and sized to your exact fit. Sizing an engagement ring consists of cutting the sizing area and either adding or removing metal to make the ring larger or smaller.

Final Thoughts

For further questions about the elements of an engagement ring, our expert jewelry specialists are always happy to answer questions and help you explore your style preferences. You can visit one of our specialists in person at one of our showrooms, by booking a virtual appointment, or by chatting with them live on our site. Have more questions about the different parts of an engagement ring? Let us know in the comments below!